***

[From The Root.com]

The Legacy of the Tulsa Race Riot

By Monée Fields-White, a Chicago-based writer who covers a wide array of topics, including business and economic news.

In 1921, Greenwood, a successful, all-black enclave in Tulsa, was the site of the deadliest race riot in U.S. history. For the inhabitants of "the Black Wall Street," life would never be the same.

[Editor's note: In time for the 90th anniversary of the Tulsa Race Riot on May 31, 2011, here's the story of a sad chapter of American history, pulled from The Root's archives.]

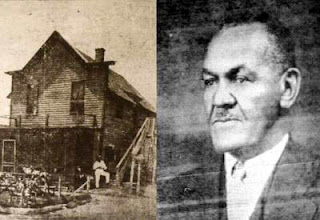

J.B. Stradford, the son of a freed Kentucky slave, rose to prominence in Oklahoma during the early 1900s as one of the key developers of the all-black Tulsa enclave Greenwood. A lawyer and businessman, Stradford owned the 65-room hotel that sat right in the heart of the thriving community that would later become known as "the Black Wall Street."

J.B. Stradford

But in a single day, all of that would change. On May 31, 1921, the arrest of a young black man on a questionable charge of assaulting a young white woman touched off the deadliest race riot in U.S. history. Whites charged through the community in retaliation, leaving an estimated 300 people dead, another 10,000 black residents homeless and 35 city blocks in ruin.

***

That 75th-anniversary year was also when the nation learned about the Tulsa Race Riot, which would come to be considered the most destructive race riot in U.S. history. "For years, silence engulfed this incident," says Hannibal B. Johnson, author of Black Wall Street: From Riot to Renaissance in Tulsa's Historic Greenwood. "In 1921, Tulsa was booming, so anything that would detract from its allure, such as the riot, was minimized."

***

White Rage Unleashed

The underlying racial and economic tension finally boiled over on May 30, 1921. Dick Rowland, a 19-year-old shoe shiner in downtown Tulsa, had gone to use the only bathroom for blacks, located at the top of an office building. He crossed paths with white elevator operator Sarah Page, 17, whom a store clerk claimed to have heard scream. The clerk said that he found a distraught Page and saw a young black man running from the building. There is no record of what Page told the police.

Rowland was arrested but never charged. The incident, however, made the front page of the Tulsa Tribune -- along with an editorial entitled, "To Lynch Negro Tonight."

Right before dawn on June 1, a mob of nearly 10,000 white men launched an all-out assault on the Greenwood District, systematically burning down every home and business. They dropped firebombs and shot at blacks from planes that had been used in World War I. Those blacks who were captured were held in internment camps around the city by the local police and National Guard units.

Martial law was eventually declared. The National Guard confirmed that 37 blacks and whites were killed, although historians (pdf) have put that number at closer to 300. Many of the dead black Americans were buried in unmarked graves around town, and some were laid to rest in an anonymous section of Tulsa's Oak Lawn cemetery. Some photographers made their pictures of the dead into postcards.

The riot "just shows you how irrelevant, not only from the view of Oklahoma but that of the nation as a whole, black life was. It was seen as expendable," says Rosa.

After the riot, black Tulsans, who were living in tents and forced to wear green identification tags in order to work downtown, still managed to turn the tragedy into triumph. Without state help, they rebuilt Greenwood, and by 1942 the community had more than 240 black-owned businesses.

Read the full article here:

***